Bud Perkins' death in a 1950 plane crash extinguished a dream

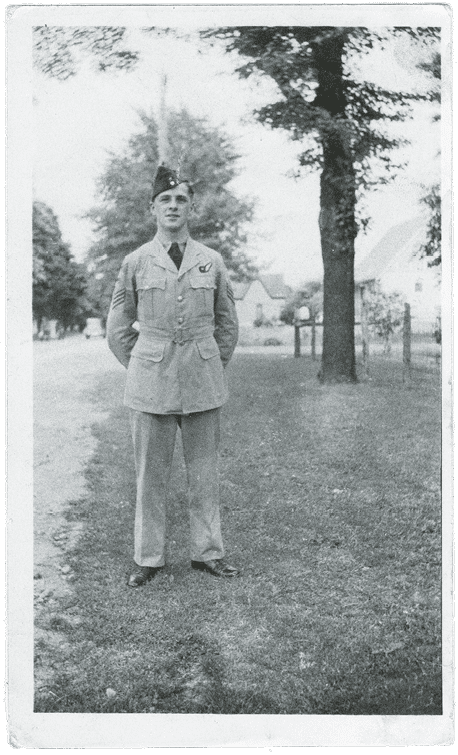

He was still a 20-year-old kid when he left his farm home in Fonthill for Niagara Falls to enlist in the RCAF, in August 1940, unsure of what lay ahead but certain that he wanted to do his part in the war that was descending upon Europe.

Coleman Douglas Perkins wanted to do it as a flier — “I hope as a fighter pilot,” he remarked in a magazine interview three years later, when he paid a brief visit home after being awarded a Commonwealth Distinguished Flying Cross for bravery and dedication to duty by King George VI, the ceremony held at Buckingham Palace.

Fighter pilots, Perkins had noted, “are the lads who have the fun and get the chance to show initiative.”

And he was determined to become one himself, not just serve as a wireless operator aboard night-flying bombers, as he had done during the two previous years, from a series of Royal Air Force bases situated along England’s North Sea coast.

Following his enlistment, Perkins had reported for training and was sent to RCAF gunnery and radio communication schools in Brandon, Manitoba, and Calgary. He graduated as a wireless operator with the rank of sergeant and was shipped overseas in July 1941.

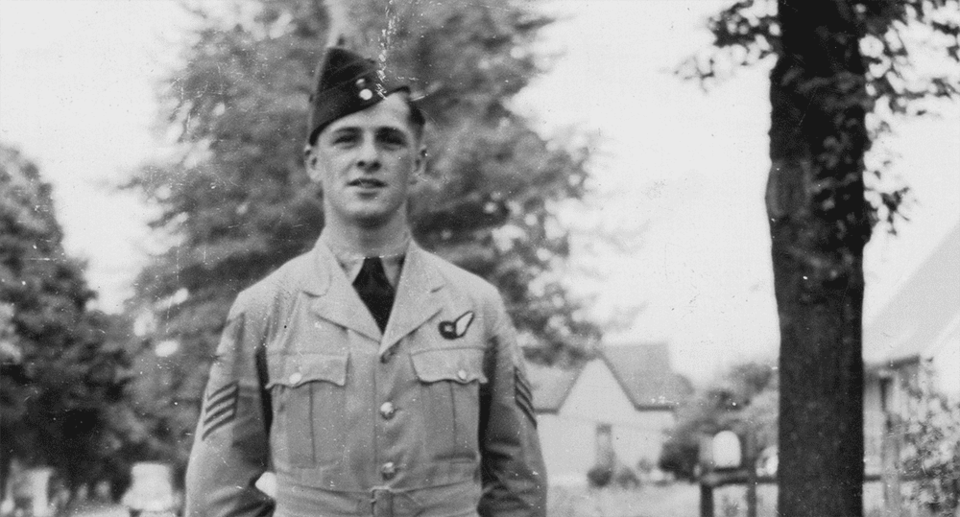

Called “Bud” by everyone who knew him, Perkins had an engaging personality, handsome features and easily made friends growing up in Fonthill.

“He was popular and well-liked by everyone,” recalled Brenda Sauer, a niece who had lived nearby in Ridgeville and who had attended SS No. 4 Pelham and later Pelham District High School before moving to St. Catharines.

Growing up herself in Pelham, Sauer was a frequent visitor at her grandparents’ farm along Highway 20, usually walking two kilometres up Haist Street from her home. More often, she helped with chores at the farm and in the Perkins’ fruit orchard. She remembers her Uncle Bud as someone who always had time for her and her same-age cousin Ginny (Virginia), who was living at the farm.

“He had a great smile and beautiful teeth,” she said.

Bud’s good looks also were an obvious social asset while attending Pelham Continuation School in Fenwick, where he was known to be a hit with the girls.

Bud was born in Woodland, Maine, and came to Canada with his brothers Hollis and Martin (Mickey) and sisters Pauline and Dorothy. His parents, John Leroy Perkins and Alice May Welton, had moved the family to Thorold in 1925 to start a new life in Canada. A family member speculated years later that John Perkins, who had been born into a large family, may have simply wanted to get away from obligations back home.

Just before the Great Depression, John Perkins, known to friends as Cy, purchased the Fonthill farm and fruit orchard while continuing to work at one of the handful of Thorold paper mills. Eventually, all of the Perkins boys, including Jim, who was born here a year before sister Bette, would be employed at the mills. For a brief period, Bud worked alongside them.

But Bud saw opportunities elsewhere, and the war in Europe offered him a chance to pursue them. His niece recalled a raft of model airplanes hanging from his bedroom ceiling, and a bulky shortwave radio on a nearby table, where Perkins eagerly followed news of the growing conflict. He had an early interest in aviation. What better chance than now to enlist, he felt.

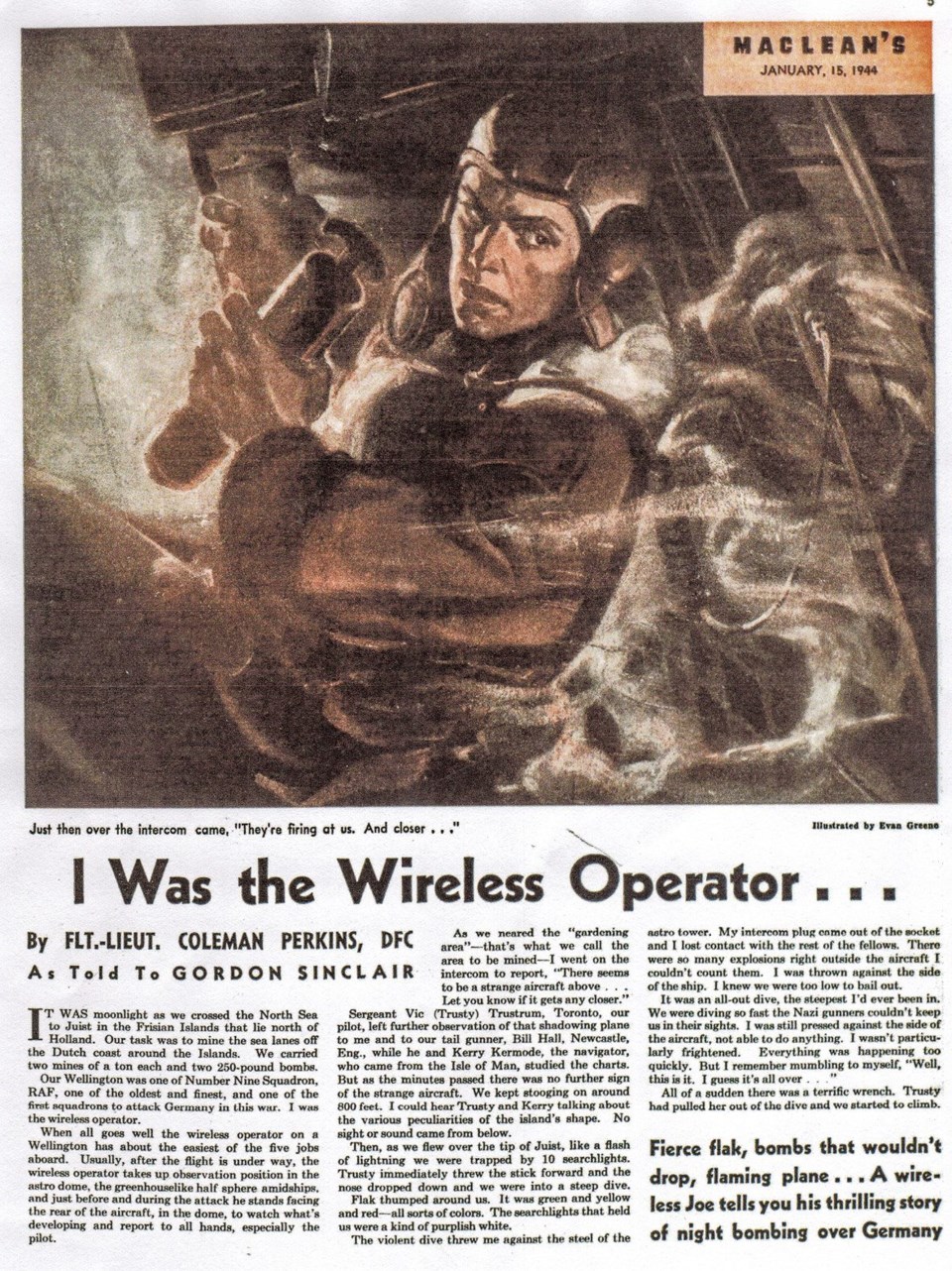

Once overseas, the young airman was quickly attached to the RAF’s No. 9 Squadron, one of a number of squadrons comprising 6 Group of Bomber Command, and assigned to crew aboard a twin-engine Vickers Wellington. The squadron, he told Maclean’s magazine writer Gordon Sinclair, while on a visit home in late 1943, “was one of the oldest and finest, and one of the first squadrons to attack Germany in the war.”

Europe was by then in the vise-grip of the Second World War, still a year and a half away from victory by the Allied forces, and bombing runs over Nazi Germany were nearing their peak. Some of Bud’s early missions were “to mine the sea lanes off the Dutch coast. We carried two mines of a ton each and two 250-pound bombs.”

Perkins recalled one night mission in particular, when the crew’s Wellington, nearing a group of Dutch islands off the North Sea coast in the moonlight, was suddenly spotted by the enemy below.

“Like a flash of lightning we were trapped by 10 searchlights. Trusty [pilot Vic Trustrum, of Toronto] immediately threw the stick forward and the nose dropped down and we were into a steep dive. Flak thumped around us. It was green and yellow and red — all sorts of colours.”

The searchlights continued to lock onto the bomber as the violent dive threw Perkins against the aircraft’s steel frame.

“My intercom plug came out of the socket and I lost contact with the rest of the fellows. There were so many explosions right outside the aircraft, I couldn’t count them,” he said. “I was thrown against the outside of the ship. But I knew we were too low to bail out.”

Caught in the grip of the bomber’s dive to evade the guns below, Perkins found himself rendered immobile, “not being able to do anything. I wasn’t particularly frightened. Everything was happening too quickly, but I remember mumbling to myself, ‘Well, this is it. I guess it’s all over….’ ”

Just then, the pilot managed to pull the Wellington out of its dive and the plane started to climb. Perkins plugged his headset cord back into the plane’s intercom in time to hear the front gunner, Joe Miesen, an American from Arkansas, shout, “Hey, I’ve got a fire here in the front turret!”

Perkins hastily picked up a nearby extinguisher and put out the flames. The thought of a fire aboard the ship made him a little shaky. “We had to lay our mines and we had to get away from there, but the most important thing to be done was to get the fire under control,” he said.

The ground firing continued as the plane weaved away.

“The flak kept going by in big red bursts,” Perkins recalled, before realizing the intercom had been shot away. “Then I heard Trusty say, ‘There seems to be something wrong with the starboard engine.’ ”

With everyone holding their breath, the Wellington proceeded down to 500 feet and the sea mines were laid. Setting out on a course to return back to their base, Trustrum found the weather less than ideal and discovered the bomber was too high for a landing approach, meaning the plane had to go around before making another try.

“Trusty pranged the throttles forward...there was a terrific shudder from the starboard engine,” Perkins recalled. “We had to stick the nose down and make a forced landing. When we got out, we found just a stub of a blade on the starboard prop. A shell had gone through her. We took 19 other hits, yet our Wellington was back in the skies two or three nights later, good as ever, out on a bombing raid.”

Receiving his DFC medal from King George, Perkins was cited for displaying “exceptional keenness and devotion to duty. He has highly efficient and courageous qualities which have made his a valuable member of [the] aircraft crew.”

The citation noted that among Bud’s “many sorties” were raids on Genoa, Turin, Munich and Berlin. He also participated in daylight attacks on Le Creusot, in France, and over Milan.

Perkins participated in a dozen more night bombing missions before reaching his required limit of 30 operational missions with his squadron, which included a transfer later to another RAF bomber base flying Avro Lancasters. He had been an active participant in 33 bombing and mine-laying sorties by then.

“If I could come home for a while and tell you all about everything, you could understand what we are up against,” Bud wrote on January 20, 1942, in a letter home to his father. But he added, “Don’t think I am complaining or feel sorry for myself. I still think I made a good bargain.”

Of all the RCAF’s operations in the war, the most costly in terms of men and aircraft had been the bombing offensive against Germany. By October 1942, the RCAF had five bomber squadrons serving with the RAF. Within three months, the bomber squadrons grew to 11 as Canadian airman serving with RAF units were transferred to distinctively RCAF squadrons.

No. 6 Group lost 100 bombers in raids over Germany. In total, 9,980 Canadians were killed in raids against German cities during 1940-45, rendering the bombing offensive as one of the most costly operations for Canada in World War II.

According to official reports, the men who served in Bomber Command faced some of the most difficult odds of anyone fighting in the war. The risks were so high that almost half of all aircrews never made it to the end of their tours.

Working alongside their British counterparts also occasionally resulted in friction, with ranking RCAF officers expressing concern over the capability of aircraft being made available to Canadian air crews, such as the Wellington bomber, considered by some to be obsolescent compared to the superior Lancaster. Canadian squadrons also were relegated to Yorkshire and Durham in the northeast, a much longer route for returning planes trying to reach their bases with their tanks running low on fuel.

As for Perkins, “I was sorry to say goodbye to that old Wellington,” he admitted, while relishing the opportunity to serve aboard a Lancaster. The plane had already been a veteran of the war when he joined the crew. The “Lanc,” he said, “was just the sort of ship I looked forward to being on when I left home to enlist.”

There had been other close calls, including a futile attempt to dislodge a flare bomb from the Wellington’s chute. The bomb was timed to explode within a minute but failed to go off. On another occasion, a 4,000-pound bomb remained stuck in a Lancaster’s bay and the plane was forced to return to base and land with the bomb aboard, a dicey prospect.

By late 1944 the RCAF had become the fourth-largest Allied air force with more than 215,000 personnel in uniform, including about 17,000 in the Women’s Division. When the war ended in 1945, more than 18,000 members of the RCAF had given their lives in the war effort.

Through it all, Perkins and his crew mates had survived when so many others had not. He was promoted to Flying Officer in January 1943, then sought permission to remuster as a pilot, his boyhood dream. That autumn, after fulfilling his tour of duty, he was shipped home to begin training.

Back in Canada, Bud spent some time with family and friends in Fonthill, and it was while there that he had agreed to be interviewed by Maclean’s. More than a month later, he was ordered to begin flight training. He was promoted to Flight Lieutenant in August 1944.

Graduating as a pilot had fulfilled his dream, but with the war nearing an end Perkins never made it back overseas flying the Lancaster bombers as he had hoped to do. Instead, the RCAF assigned him to flight training as an instructor. It may not have suited him, because he retired from the service in January 1946.

A civilian again, Perkins decided to pursue a career in forestry with the Ontario Lands and Forests Department. Taking advantage of his combat veterans’ benefits, he enrolled at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, which allowed him an opportunity to visit his parents’ families in Maine. He bought a 1949 Dodge convertible and had it painted Air Force blue.

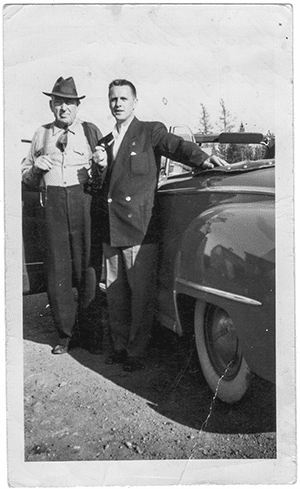

A 1948 family photo shows Perkins on one such trip into Maine, standing alongside his maternal grandfather, Welton, Bud looking dapper in a dark blazer and grey slacks with a hand placed on the open top of his convertible.

“He picked Ginny and me up in the car one day and we rode to Welland with the top down,” recalled Sauer, who was eight or nine years old at the time. “We sat — or, I should say, stood — in the back seat like a couple of beauty queens riding in that car. He was like that — happy-go-lucky, always smiling or laughing. He was very proud of that car.”

Following his university graduation, Bud secured a map-making position with Lands and Forests, a job that also would have likely allowed him to fly on occasion. Bud soon began taking aerial photos of the province’s vast north and using them to create topographic maps. On these flights, however, he was a passenger, not the pilot.

It was one of these assignments, on June 30, 1950, that nearly cost him his life. Perkins was part of a four-member forestry crew, including the pilot, when their de Havilland DHC-2 Beaver crashed near Temagami, 80 kilometres north of North Bay, after the engine cut out without warning. No one was seriously hurt and Bud told his family later that the accident hadn’t fazed him.

“My mother told me that Bud had jumped before it hit the ground,” Sauer recalled. “He didn’t break anything. He just jumped and that was it.”

A Canadian Press report at the time said the four men spent the night in a makeshift tent “on top off the slope on which the plane had crashed.”

But Bud’s luck ran out two months later. Another Provincial Air Service aircraft, a Noorduyn Norseman, crashed and burned August 30, while attempting to land on a small lake, again near Temagami, killing Perkins and four other department staff. Four of the men had been RCAF veterans.

The single-engine floatplane was carrying a small tractor and may have been overloaded, although investigators blamed engine failure at low altitude. The resulting fire was so intense that it was difficult for investigators to identify the charred bodies, although Perkins’ family was told later that Bud, who had been wearing a leather jacket, had covered his face with an arm just as the plane crashed, so that part of his face was recognizable.

One of the dead passengers left behind a wife and five children. Bud, who was engaged to be married, would have turned 31 in less than a month.

Back in Fonthill, the family took the news hard. Charlie Haist, a neighbour and friend, dropped by to comfort Bud’s mother, shooing young Brenda and Ginny outside and asking if there was any whisky or brandy in the house. Alice May was inconsolable. John Leroy was his usual stoic self.

A funeral was held in town on September 2, a Saturday, drawing a large number of family and friends to the Drake and Barron Funeral Home on Pelham Street. Members of the Lands and Forests Department formed a guard of honour. There were so many bouquets of flowers at the funeral home, recalled Bud’s niece, that it took two vehicles to transport them to Fonthill Cemetery.

Sauer said that just before Bud’s funeral, Alice May had been discovered at night walking in her nightgown while carrying a blanket along Highway 20 to the funeral home.

“She told the family later that it had been cold that night and she wanted to cover Bud up.”

As for John Leroy, he had Bud’s Dodge convertible driven back from North Bay. Later, he paid a goodly sum to have the car’s fenders and sills completely leaded to prevent corrosion.

“On any Sunday, if the weather was fine, Grandpa would dress up in his suit and tie, put on his Panama straw hat, and drive Bud’s car out in the country,” Sauer remembered. “The family made a great deal of fun over this.”

Years later the car would be auctioned off for $1,000.

And Gordon Sinclair, who had interviewed Bud for Maclean’s when he had returned home in late 1943, would achieve fame as a globe-trotting Toronto Star reporter, best-selling author, radio commentator and eventually (with some notoriety) a TV panelist on the CBC show Front Page Challenge.

Perkins, who had visited his Fenwick high school on several occasions while home in 1943 to speak to students about his war experiences, might have recalled a few lines of a Wordsworth poem from his English Lit class:

What though the radiance which was once so bright

Be now for ever taken from my sight...

And the ones that followed:

Though nothing can bring back the hour

Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower,

We will grieve not, rather find

Strength is what remains behind...

They would have provided a fitting epitaph to Bud’s short life. ◆

Bill Eluchok is a former editor and reporter with The London Free Press. He lives in Welland.