In case you missed it, in his latest Balanced Life column, John Swart gets bookish:

Thirty years ago, Richard Shuh, co-owner of Alphabet Bookshop in Port Colborne, was at a book fair in New York City with his friend Jeff, a bookseller and lawyer from Rochester, New York. Jeff received a phone call saying, “There’s a house-full of books here, the family wants the house cleaned out, and our current bid on the house contents is $2000.”

Jeff happened to know the family, relaying to Shuh that the guy was a wacky bookseller and antique collector, and the house was a treasure trove. They bid $12,000 for the contents.

“There was no other bid for anything close to that,” said Shuh, “so Jeff and I bought the contents of the house sight unseen. Linda [Shuh’s wife and partner] and I moved to Rochester for a month, lived in a motel and we emptied out the house. It was full of antiques. Jeff or Linda or I knew nothing about antiques, yet here we were pulling out all this glass and china and putting it on the porch at night. In the morning it would be gone. Later on we learned it was worth $50 or $100 each. In 30 days we swept the place clean and threw out two 28-foot industrial dumpsters full of books.” Shuh has the photographs to prove it.

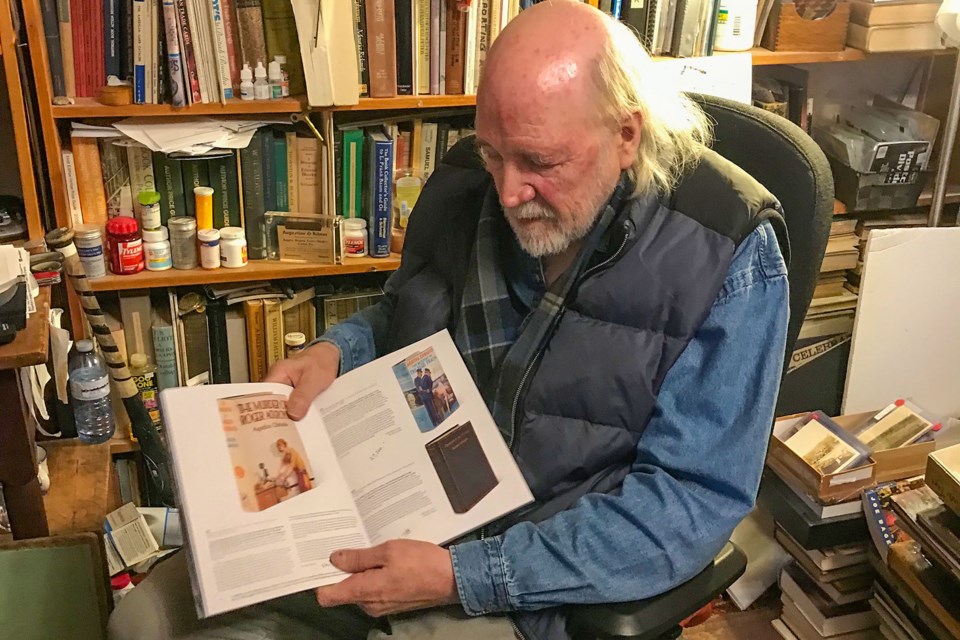

Richard Shuh and Linda Wooley are not typical booksellers, and Alphabet Bookshop is no typical used bookstore. Shuh’s bio states that he is “a full-time professional, antiquarian bookseller...qualified to provide appraisals for Cultural Properties, for library donations (for tax purposes) and for private insurance purposes.”

He is a member and past-president of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of Canada (ABAC), the Ephemera Society of Canada, and the International League of Booksellers. He has done cultural appraisals for the National Library of Canada and others, including yearly appraisals of Margaret Atwood’s donations of papers to the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, the largest repository of publicly accessible rare books and manuscripts in Canada.

Shuh explains that ABAC is a professional association rather than a trade association. He details the qualifications, including creating extensive detailed bibliographies for numerous relevant authors, and the peer approval process required to become a member, which in his case was enhanced by selling the only known original copy of Robert W. Service’s 1907 book, Songs of a Sourdough.

Regarding the integrity of ABAC’s Code of Ethics, he says emphatically, and refreshingly in today’s world, “If you break it, you’re out.”

Shuh has been in the antiquarian book trade for 38 years, so I asked what seemed obvious, “How did you come to this, a love of history, a love of books?”

“Oh no, no. I didn’t want to go to school anymore. I was in a law stream, and I disliked lawyers and the law, and I wasn’t fit to be a teacher. I’d always had an interest in books, and I had a lot of books that I’d bought at yard sales and stuff like that. It was an accumulation that followed me around for years and years, I had 5000 or so.”

Shuh met Wooley at Lakehead University, in Thunder Bay, where they were students. They moved to Toronto and she took a job at York University.

“One day our apartment was full of books and she walked down to Harvard and Spadina, the university area, and there was a store for rent. She walked in and rented it then came home and said ‘You’re opening a store tomorrow.’”

Your columnist’s two pages of carefully prepared questions about the book business in the digital age were fading toward irrelevancy as our conversation bounced between Shuh’s entertaining personal reminiscences and his astonishing recollection of facts about the thousands of books that have passed through the store. In hopes of eliciting another fun tale, rather than ask Shuh’s opinion of the future of Indigo Chapters or something equally mundane, I ask instead, “What’s your best find?”

He takes a few seconds, clearly scrolling through his cache of memories, then begins. “There’d be a few.”

The internet killed the ordinary books under $500 because anyone could look them up

He details how Marty, a retired Finnish bookseller and mentor from Toronto, became a book scout, travelling Ontario and beyond searching for books that other sellers might want. Marty called Shuh from an antique store in Kingston one day, saying he had found a Faulkner published in Britain, The Sound and the Fury, in pristine condition, for $600. Shuh guessed it would retail for $800, so suggested Marty not purchase it. A few months later Marty visited the shop again, and negotiated the price down to $500.

“Now Marty has the book in his hands, and notices the publisher was Harrison Smith and Robert Haas, an American publisher. This was actually an American edition of the book.” Marty bought the book. Shuh gave Marty the $500, and “about five days later, Marty and I both bought brand new vans from the sale of it. The British edition was published a couple years later, but the American one had a red spine. Red is a colour that fades very easily. To find an unfaded red one…”

Shuh says that the internet has had a significant impact on used book retailing, and antiquarian book sellers specifically. He describes how many older books and classics are being reprinted by Amazon and others in hard copy and digitally, making the need to find an original copy for reading purposes unnecessary. Manually searching paper book catalogues is a thing of the past for readers too.

Venturing to Alphabet Bookshop’s website links you to AbeBooks, a global e-commerce bookseller featuring academic books—one of three that provide the Port Colborne store an international customer base.

However, Shuh says, “The internet killed the ordinary books under $500 because anyone could look them up.” He recalls the days booksellers lined up to buy a library closeout, but says now you can’t give most old books away, in part because anyone with a computer can search for values now— within limits. “Books worth more than [$500] kept their value, because booksellers often didn’t put them on the internet.”

Relatively recent books have potential to be valuable too. Signed copies are big, and there are people who collect only an author’s first book. When a book blows up with success, signed copies that may have been autographed at a book-signing early in an author’s career can become extremely valuable. Think J. K. Rolling and the Harry Potter series, or our own Alice Munro, whose first book in 1967, Dance of the Happy Shades, won the Governor General’s Award. An original copy is now worth $1000.

Shuh catches me glancing at an ornate 19th century family bible sitting nearby, which moves him to share his own bible story of sorts. He tells of a woman who came to the shop to sell her family bible. It was beyond repair and had no value. The distressed woman couldn’t handle throwing it in the garbage, so she left it on the counter. Shuh examined it a few days later and found that it had a piece of paper in it which was printed on one side—a broadsheet. “After I had researched it for a couple weeks, I discovered that the broadsheet was the first thing ever printed west of the Mississippi River in America. Someone hauled a printing press across the Mississippi while traveling west, and as he went he printed religious broadsides. This was the first one he produced. There are only four known copies in the world. I sold it for a couple thousand dollars and I’ve never seen the woman again. I have no idea who she is.”

We haven’t yet discussed the bookshop’s ephemera collections —old and historic photographs, postcards, single-use paper items no longer being produced. How Shuh and a Hamilton book dealer brought paper ephemera collecting to Canada, and how it took ten years to get a grasp on the items’ values.

I ask if ephemera still a thing, and Shuh responds, “Oh yes, it’s crazy now, it’s sort of the latest thing, especially among people who live in condos. They can buy large quantities of stuff and keep it in a small box, thousands of dollars of stuff.”

At my feet is a poster from the ‘60s featuring Janis Joplin while she was still the lead singer with Big Brother and the Holding Company.

Then there’s the corner dedicated to first pressing LP records—jazz, rock, counter-culture—and another area filled with current detective and mystery novels. There are no recent romance novels in the store, Shuh says without judgment, or not.

This store is anything but a random picker’s venue, everything here connects. Customers come from everywhere and all walks of life— Brock students anxious to read beyond course-required books to the couple from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania that make the trek regularly to spend a few hours in the store.

A 1918-1921 Kodak model 3A “Autograph” camera sits perched on folders in an opened drawer of Shuh’s desk during our conversation. He explains how it works, clicks the shutter release to show this one is in particularly good shape, and how he’ll be able to repair a couple tiny tears in its bellows himself.

I ask how long he’s been into cameras, and he replies with an anecdote. “I knew nothing about old cameras two years ago. Some came up for sale at auction, I bought the box for $450, brought them home.” He did okay on them, bought some more, and now Shuh finds them endlessly interesting because of their technology.

The onslaught of stories sneaks up on you, but then you realize each one is has a purpose— to communicate Shuh’s incredible knowledge of books in an entertaining style, to add colour and meaning to the aged books and ephemera surrounding us, or to share the richness of the lives that created the shop.

“I get up every morning and it’s not a matter of something to do,” says Shuh, “it’s a matter of what to do first.” This bookseller’s philosophy is hard to disagree with.