There is something grimly predictable about accusations and proven cases of clergy abuse. I say this with a heart lead-heavy because I’m a priest, and each time a cleric is named or shamed I suppose I die a little inside. Just these past few months one of Canada’s largest mega-churches, The Meeting House, has been devastated by news of firings, old convictions, and new criminal charges. I’m not qualified to discuss the details of this 5000-strong Anabaptist institution, and with full disclosure acknowledge that I know Bruxy Cavey, the dismissed teaching pastor and guiding spirit of the church.

But it’s about far more than this case. Ravi Zacharias was an Indian-born Canadian-American evangelical author, who earned his undergraduate degree from what was then Ontario Bible College. He wrote some 30 books, was a world-renowned Christian apologist, and was welcomed by world leaders. There had been allegations of wrongdoing while he was alive, but after his death in 2020 his own organization confirmed cases of serious sexual misconduct.

Canadian Catholic guru Jean Vanier, whose work with people with developmental disabilities transformed countless lives, was regarded as a virtual saint. In early 2020, however, an internal report concluded that he had sexually abused six women in France between 1970 and 2005.

Then we have the sordid, morbid case of residential schools in this country, and the still unfolding horror story of Canadian Catholic priests abusing children. Both of these stories took far too long to be brought to light and justice. Multiply this myriad times in other nations, at other times, and the darkness becomes ever more clawing. The Southern Baptist Convention, America’s largest Protestant denomination and one known for its conservatism, is currently facing what one leader described as an “apocalypse” due to a 205-page document naming hundreds of leaders and members as child abusers.

So, this obscenity isn’t confined to any one church, and while Roman Catholicism may have its own systemic problems, the real issue here is more far-reaching. There are, of course, those who will attribute all of this to religion itself — the same sort of people who regularly accuse me of being a pedophile on social media because I wear a collar and disagree with their opinions. That’s simply foolish and naïve. The bitter, biting reality is that abuse occurs whenever there is a power dynamic capable of distortion, which is why it’s so common in families, schools, and sports teams. In fact, pretty much everywhere.

There are various factors within organized religion but one of the main causes is, I believe, the error of clerical elitism. The cult of the leader — invariably male — who is perceived as almost representing and sometimes even replacing God. The charismatic pastor or priest regarded as royalty, ordained by the almighty, who can do no wrong because he’s infallible. Father says this, pastor says that, and the rest of the nonsense. In many cases the abused were told that this was God’s plan, and what was happening couldn’t be unethical or illegal because nothing flawed came from the creator.

There are various factors within organized religion but one of the main causes is, I believe, the error of clerical elitism

It’s truly hideous, not only because of the abuse itself but also due to the exploitation of people who are often deeply vulnerable. In my three years ordained I’ve seen more pain and suffering, and consequent trust and need, than I ever thought possible. That can be exploited by the unscrupulous if they’re allowed to develop too much self-regard. Which is why clergy have to be reminded of who and what they are on a regular basis. Humanity through humility.

We as clergy can point the way, can turn on some lights, and certainly be present in times of desperation. But we’re as much fellow travelers as journey leaders, and frequently the ones doing the learning.

For example, I’ve visited numerous people in hospital as a priest but had never actually been an overnight patient. I was one last week, for a minor if fairly long surgery. That was authentic formation—3 AM, sleepless, broken, uncomfortable, and, if I’m honest, frightened. That’s where the cleric should be. Never in total control, never the one with all of the answers, and always looking to others.

Abuse is the most bloody and bruised result of arrogance and pride, and both of those sins — yes, we in the church still believe that sin exists — are open wounds. People abuse for many reasons but often because they think they’re above others, and beyond common morality. With clergy, they dare to think they’re divine. God forgive them!

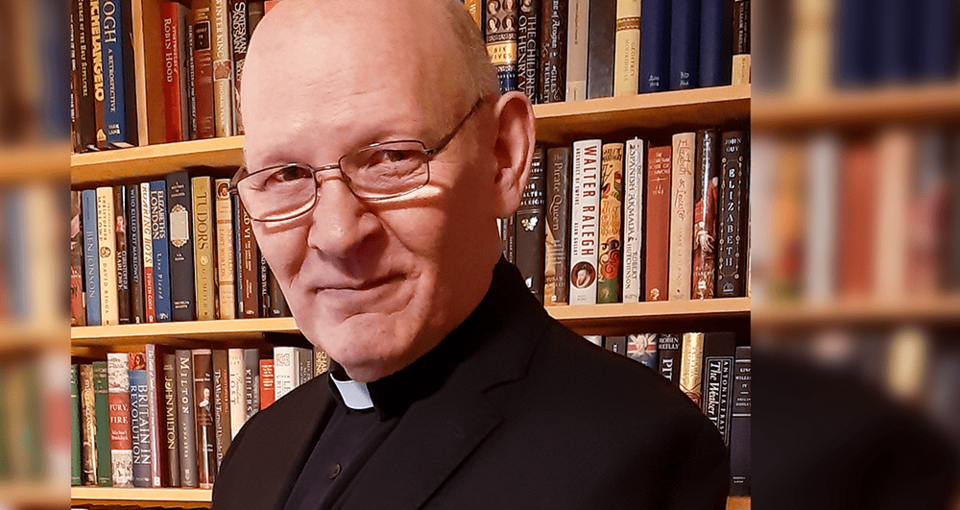

Rev. Michael Coren is an award-winning Toronto-based columnist and author of 18 books, appears regularly on TV and radio, and is also an Anglican priest.