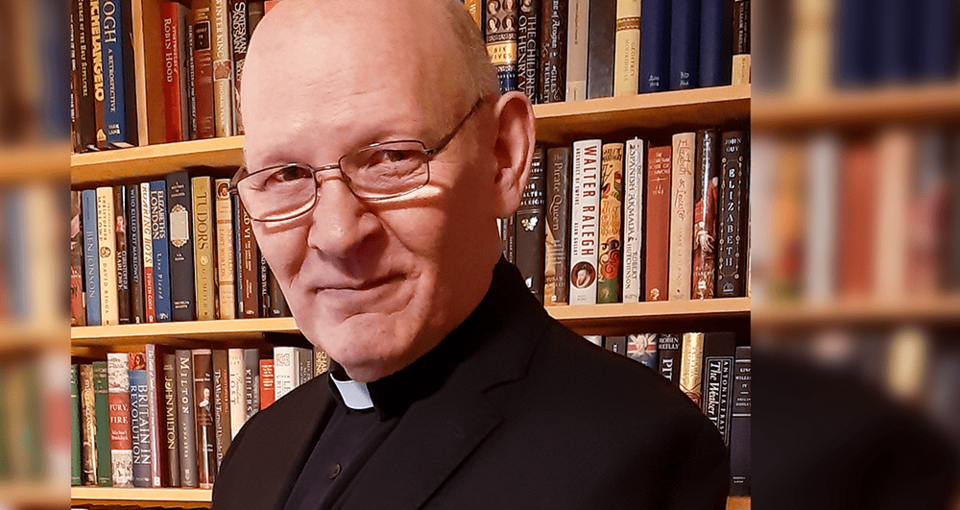

I’ve been an ordained Anglican cleric for three years and conducted numerous ceremonies but never before have I presided over a baptism in the morning, and a funeral in the afternoon. That occurred in mid-July, and while I won’t name those involved for obvious reasons I do want to discuss what such a meeting of emotions, a pairing of beginning and conclusions, says about all of us. Because it says, whatever our beliefs, quite a lot.

You see, if we’re honest about it all, the human condition isn’t in a very good place right now. Wars, conflicts, western societies polarized as they’ve not been for more than half a century, and a social media and a political culture that despises moderation and forgiveness, and celebrates extremes and denunciations.

But what, we may ask, has this got to with a church and its ceremonies? Fair enough. The answer, however, is deeper and sharper than you might think. The hopes and aspirations of loving parents, the pain and loneliness of grieving children and partners. The living, breathing human narrative, in all of its endless fragility and its constant beauty.

The precious borders of our lives, their beginnings and their ends, should open us up, revealing intimacy and vulnerability, leading us to question our actions and filter our emotions and feelings through a prism of goodness and kindness. The observation of the significant, be it a baptism, a wedding, or a death, becomes a catalyst for our self-awareness.

People of faith have prayer at the centre of our lives, and in so doing we let go, allow, and accept. In a way, it’s a profound acquiescence, perhaps a reluctant acceptance that we may not know what is best and that there is someone above and beyond us. Then comes the superb paradox for those of us who are Christian, that in defeat is victory, and in death is life. So bitingly contrary to a world that increasingly celebrates wealth, power, and prestige, no matter what the cost.

For me, baptisms and funerals sing tunes of selflessness, the abandonment of the ego, and the gorgeous acknowledgment that we’re all — religious or not — part of a physical and a spiritual collective. The philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaard once said that we can “creep into God.” That’s very good indeed. Creep into God, slowly and sometimes without us even being aware of it. Especially now, when the deity, or at least many of his followers, often have such a poor reputation. Take it slowly, take in gradually, and never rush things.

None of this is completely transparent or even obvious, but then God seldom does the transparent or the obvious. What the almighty does do is to remind us that we can be better and do better, and that in our smiles of welcome and tears of farewell we can help to make the world the place it could and ought to be.

We have merely a few decades on earth to make a difference, and it doesn’t have to be one that is recorded in history books or make the news

What should form us isn’t the stock market but the market of generosity and care, not the speeches of politicians but the sacrifices of ordinary people, not the empty hysteria of reality television and show business flamboyance but the full and gritty grace of those who anonymously perform the thousand small miracles that keep optimism alive.

We have merely a few decades on earth to make a difference, and it doesn’t have to be one that is recorded in history books or make the news. I’ve met too many genuine saints, largely unknown beyond their family and community, to believe otherwise. The world can be changed, often is changed, by one person and one action at a time.

I was baptized as an adult, in my mid-20s, and in one of those strange turns of fate my grandfather died just two days later. He’d been ill for some and I was with him in his final moments. This tough, hardened man, who’d seen years of war in the British Army, and hardship and poverty growing up in the east-end of London, gave me a smile shortly before he closed his eyes for the last time. As he did so, he said through deep and strained breaths, “Mike, some things matter, some things always matter.”

He was right. Some things really do. Welcome to the precious baby, goodnight to the beloved deceased. You matter, and always will. If we remind ourselves of that fact, and continue to do so, perhaps there might be a brighter, lighter future for all of us. Let’s hope and pray so.