Aviator, author, member of the Order of Canada, to be celebrated on March 24

Dorothy Wetherald Rungeling, the lifelong Pelham resident who was awarded the Order of Canada in 2003 for her feats in aviation, died on February 17.

Rungeling was born Helen Maude Doane in 1911 and was adopted by the writer Ethelwyn Wetherald, who renamed her Dorothy and with whom she grew up on a farm in Fenwick.

In 1927 she got her driver’s license; in 1949 she became a pilot, eventually winning several races and setting records as the first female to accomplish various feats.

Rungeling’s introduction to flying was an accident. In 1951, she wrote of herself as having been “a woman who was terrified of airplanes. To her, they were machines of the devil flown by demented fools who could find nothing better to do with their time. They killed people without any provocation whatever, they just fell out of the sky for no reason at all, and they were just as likely to disintegrate before your eyes in flight as not.”

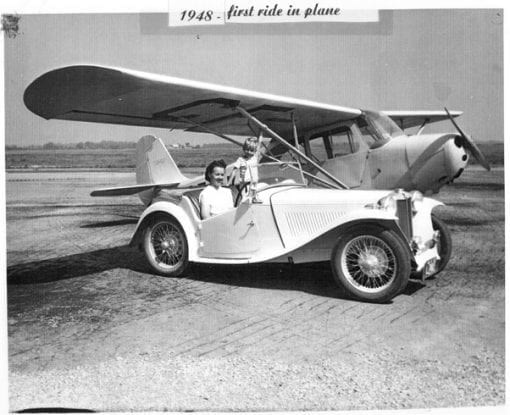

Rungeling and her husband, Charlie—an Englishman who had come to Canada to work—owned a car garage, and she wrote that Charlie had the “bright idea to have one of the little English cars we sold photographed under the wing of an airplane to use in advertising.”

When at the airport for the photo shoot, their four-year-old son Barry wanted to go up for a ride, as did Charlie.

“It was certainly goodbye to my family forever. They would never come down alive,” wrote Rungeling.

When the two did come down safely, Barry badgered his mother into taking her own turn.

“As I climbed into the little hell-machine I borrowed Charlie’s handkerchief because I knew I would be sick,” she recalled. But she wasn’t. The flight transfixed her.

“We went home to the supper I had mentioned an hour before. Only I didn’t feel like getting supper now. I was too busy thinking about that airplane and those dials on the ‘dash’ and about how slow you went so fast,” she said. “Somehow the old world seemed very drab and unexciting. Something was wrong…something was missing…or had I been missing something?”

A week later, Rungeling returned to the airport without telling her family.

“Nobody knew I was learning to fly because I thought everybody would be against it,” Rungeling told the Voice before her 106th birthday party last year. “But they weren’t.”

Six hours of lessons later and she was flying a plane solo. Charlie was ultimately supportive of her piloting, and the two soon bought the first of a series of their own planes.

Rungeling became known as “Canada’s Flying Housewife,” winning numerous races, including the Governor General’s Cup in 1953 and 1955, and a race from Hamilton to Havana in 1954.

She joined the Ninety-Nines, an organization of female pilots, and in 1954 was the first Canadian woman to earn an Airline Transport License. She competed three times in the All-Woman Transcontinental Air Race, which was nicknamed the Powder Puff Derby. She and her co-pilots once wore matching aprons embroidered with the words: “To hell with housework.”

Rungeling was also the first Canadian woman to conduct a solo helicopter flight, and in 1964 was elected Pelham’s first female Town Councillor.

In 2015 the airport at the southern reach of Pelham was renamed after her, though a lack of funds has meant that signage with Rungeling’s name has yet to be erected. Pelham Town Councillor and chair of the airport commission, Richard Rybiak, recently told the Welland Tribune that the signs will be done “as soon as we have the capital funds available for the project.”

Though Rungeling last flew a plane decades ago, her deep love for being airborne never left. When she was 101, a young acquaintance of hers remarked that he had a friend who’d be interested in taking Rungeling up for a spin in his two-seater.

“Oh, I’ve had lots of chances to go up,” said Rungeling. “I always say no. I’m afraid I’ll catch the bug again.”

There was one time when Rungeling did return to the sky. The man to whom she had sold her last plane still had it in Grimsby. After Charlie died, Rungeling went up in it one final time. Helgi Kernaghan, who knew Rungeling for 50 years, drove with her to the airport.

“She said that it was nice to take a ride in it, for the memories,” said Kernaghan. “But she didn’t have the itch to fly again.”

Kernaghan and her husband Ken bought the Rungelings’ Foss Road farm in 1968. Rungeling had first come to that farm with her birth mother in 1911, when she was six months old, and she later wrote that when the property was sold to the Kernaghans, “we did not have a door key to hand over.”

“It was a working farm [in 1911],” said Kernaghan, “and her birth mother had come from Toronto to work. Eventually, they decided that it would be better for Dot to grow up on the farm there. When she was two or three, Ethelwyn adopted her.”

Despite being adopted by Wetherald, whom she called Nan, Rungeling remained in contact with her birth mother Mary Doane, whom she called ‘Mama.’ Until Mary’s accidental death when Rungeling was a teenager, Rungeling regularly visited her in Toronto.

“After looking forward all year to summer holidays so I could visit the big city, when the time actually arrived I was hesitant about going,” Rungeling wrote a lifetime later. “Going to the station in a horse and buggy gave me more time to think about it than I wanted. But even at the age of eight or nine, I felt the responsibility of keeping my part of the bargain. It was good practice in what I had been taught—that responsibilities and promises were something to always be honoured.”

Rungeling said that her apprehension soon dissipated upon arriving in the city.

“As if by magic we entered a dark, shadowy world. It was an eerie feeling to look up on either side and see nothing but tall buildings which cast very dark shadows and gave a feeling of nightfall—of being dwarfed, of being just a little bit scared, and I hung onto Mama’s hand a little tighter.”

When Rungeling was eight or nine, she spent a Christmas in Toronto. “[Mama] had been experiencing a particularly bad time with employment and was living in one room,” wrote Rungeling. “She did her best to give me a good time while I was with her, but soon all her money was gone and Christmas was upon us. I somehow realized that she had a financial problem and I knew enough not to expect a Christmas present—not even one. On this Christmas morning when I woke up, I fully expected that it would be just another day, and I was prepared to accept it as such. Everything would be all right.”

When Rungeling awoke in the morning, there was a small bundle at the end of the bed.

“My mother smiled and said: ‘It’s yours. Open it. And Happy Christmas!’ There were tears in her eyes,” wrote Rungeling. “There lay a tatting shuttle. I was overjoyed. The world was right! I had a tatting shuttle!”

“I appreciated the situation more and more and years went by. I had received the best gift in the world—a gift of love and a mother’s tenacity in getting a gift for her child, no matter how small or inexpensive it was.”

When she published her first book, in 2001, Mary was the first person mentioned in the dedication.

“To my birth mother Mary, who unselfishly shared her child to give me opportunities that would otherwise have been impossible,” wrote Rungeling. She thanked Wetherald too, who she said “even in the early 1900s taught me not to ‘follow the crowd,’ but to be my own person and follow my dreams.”

Wetherald was in her mid-50s when she adopted Rungeling—of this, Rungeling wrote only, “She had many family problems that she did not share with anyone.”

Rungeling recollects her as being truly kind. In one story, Rungeling wrote of a time when she cut up her Uncle Herbert’s reins in order to make a skipping rope. Herbert was furious, according to Rungeling, and demanded that Wetherald spank her, something that had never before happened.

As Wetherald was about to strike, she whispered in her daughter’s ear. “I won’t hit you hard,” she said. “You just holler good and loud and Herbert won’t know the difference.”

Wetherald died of pneumonia in 1940. Her last words to Rungeling were, “I’m so glad I adopted you.”

Last week, Helgi Kernaghan said that one of Rungeling’s disappointments was that Wetherald had not achieved greater local recognition for her accomplished writing career.

Kernaghan was Rungeling’s guest at the Order of Canada ceremony in 2003, where Rungeling gave an impromptu speech.

“She gave a little bit of her history, and told a few stories,” said Kernaghan. “I think that she told the one about the car stalling.” For Kernaghan the car-stalling story was representative of Rungeling.

“Dot was ahead of her time when it came to the women’s movement,” said Kernaghan. “There were lots of men at the airport who weren’t too happy that a woman was there flying, and winning all those races too. Dot said that one day they did something to her car so that it would stall soon after she left the airport. But Dot knew all about cars—so she fixed the problem and then did a lap back around to the airport, just to say to them, ‘You can’t stop me.’”

But regardless of resistance she faced, Rungeling was never one to complain about her treatment.

“It is my opinion, regardless of Women’s Lib, that in the early 1900s there wasn’t much that a woman could not do if she really wanted to. The only reason she did refrain from taking part in some these things is that she was afraid of being an individual,” wrote Rungeling.

Through it all, Rungeling readily credited those around her for allowing her such liberation.

“My beloved husband Charlie,” she thanked in a book dedication, for making “my dreams come true with his unfailing encouragement and his ever-present ‘Go for it! You can do it.’”

Charlie supported her early motorcycle habit—she bought her first bike for $50 in the 1930s—and her skeet-shooting and horse-riding interests too.

Rungeling learned to play the clarinet, saxophone, and harmonica, and was a first violinist in the Cornwall Symphony Orchestra. She became an avid amateur artist, making pencil sketches of Pelham from the early 20th century, and working with watercolours and acrylics.

When Rungeling finally gave up flying, she and Charlie became active sailors. Soon after, Rungeling demonstrated her wicked wit in a brief pamphlet satirizing the many technical terms used by sailors.

“This is dedicated to the new sailor, who I am sure is having just as hilarious a time understanding the nautical lingo as I am,” wrote Rungeling, before listing her own definitions for various terms.

“Pinching: An Italian compliment,” was one entry.

“Skin Drag: A dance at a nudist colony,” and “Yacht: A hole in the water lined with mahogany into which one puts hundred dollar bills,” were others.

Lorna Brandstatter, whose father went to school with Rungeling, knew her for 78 years.

“We moved back to Welland from Oshawa when I was about two,” said Brandstatter. “We called her husband ‘Uncle Charlie,’ and Dot told me that he used to pick me up and carry me around.”

“One time, Uncle Charlie took me out on the horse and cutter in the winter. I still remember the bells on the horses and the way the snow rolled off their hoofs. That’s one of my favourite memories. When I told Dot about it, many years later, she said, ‘Oh, that horse would have been Sydney. She loved driving the cutter.’”

Brandstatter was still quite young when Rungeling got her pilot’s license, but was nonetheless enthralled when she was taken up for a ride.

“She pointed to a hole in the clouds and said that it was a ‘Sucker Hole,’ because you’re a sucker if you go up there,” recalled Brandstatter.

When Rungeling’s husband was in the hospital before his death two decades ago, Brandstatter began calling Rungeling twice a day.

“I’d call her to make sure that she got home from the hospital all right, and then I’d call her in the morning to make sure that she was okay,” said Brandstatter. The two spoke twice a day for the next 20 years.

Rungeling enjoyed good health well after her 100th birthday, turning in her driver’s license only when she was 102. She bought her first computer in 1991, at age 80. “This was before Windows...before almost anything which we now have on personal computers,” she said. “It had a program named Norton Desktop.” She became proficient with the machines, and eventually gave lessons to other seniors.

In her 90s she authored several books, including three compilations of stories from her life, even titling one, “It’s Fun to Grow Old.”

Though she outlived all of her contemporaries, Rungeling continued to make new friends, particularly at Lookout Ridge Retirement Home where she resided during her final years. A memorial service will be held there on March 24, at 2 PM.

Friends of Rungeling are expecting many people to attend, considering her presence and prominence in the community in which she lived for more than a century, and which she loved dearly.

“So when I die, I will have seen ‘the best show on earth,’” she wrote in the introduction to stories from her childhood about the place that she loved.

“I will have lived to the utmost, enjoyed to the fullest all the marvellous developments of mankind, while still being able to enjoy the things people used to enjoy—the marvels of the sky, the clouds, the trees, birds, and other things of Nature’s creation, because this was my beginning.”

Rungeling’s friend Mary Beattie, whom she saw regularly for the last 25 years of her life, was with Rungeling in the hours before her death. Beattie said Rungeling was lucid up until the last.

Late Saturday afternoon, Rungeling was resting in bed as Beattie visited. Beattie said that she asked Rungeling if she was comfortable.

“Yes, very comfortable,” replied Rungeling. “I just need to close my eyes, and go to sleep.”